The conference demo playbook is broken

In Finding your AI North Star, I wrote about identifying friction and building solutions that actually matter. But I stopped short of the next problem: even when we find the right solution, we can still fail if we can’t tell the story.

I’ve seen it, so have you: jargon-first. Buried value. Losing the audience in three minutes.

This piece is about storytelling. Not marketing (that’s not my expertise), but the kind of storytelling that makes people care about what you built. Some of you already do this well. For the rest of us: let’s talk about what doesn’t work, and how to fix it.

You’ve all seen this demo

FancyCloud is a fantasy cloud company who has just developed this incredible use case for AI. They’ve designed a predictive architecture framework that can analyze existing workload patterns for a given customer, and determine the most efficient combination of on-prem, hybrid cloud, virtualized, cloud native and fully managed deployments to maximize responsiveness, minimize spend, and virtually eliminate downtime. The hero everybody asked for!

Here’s how the demo goes:

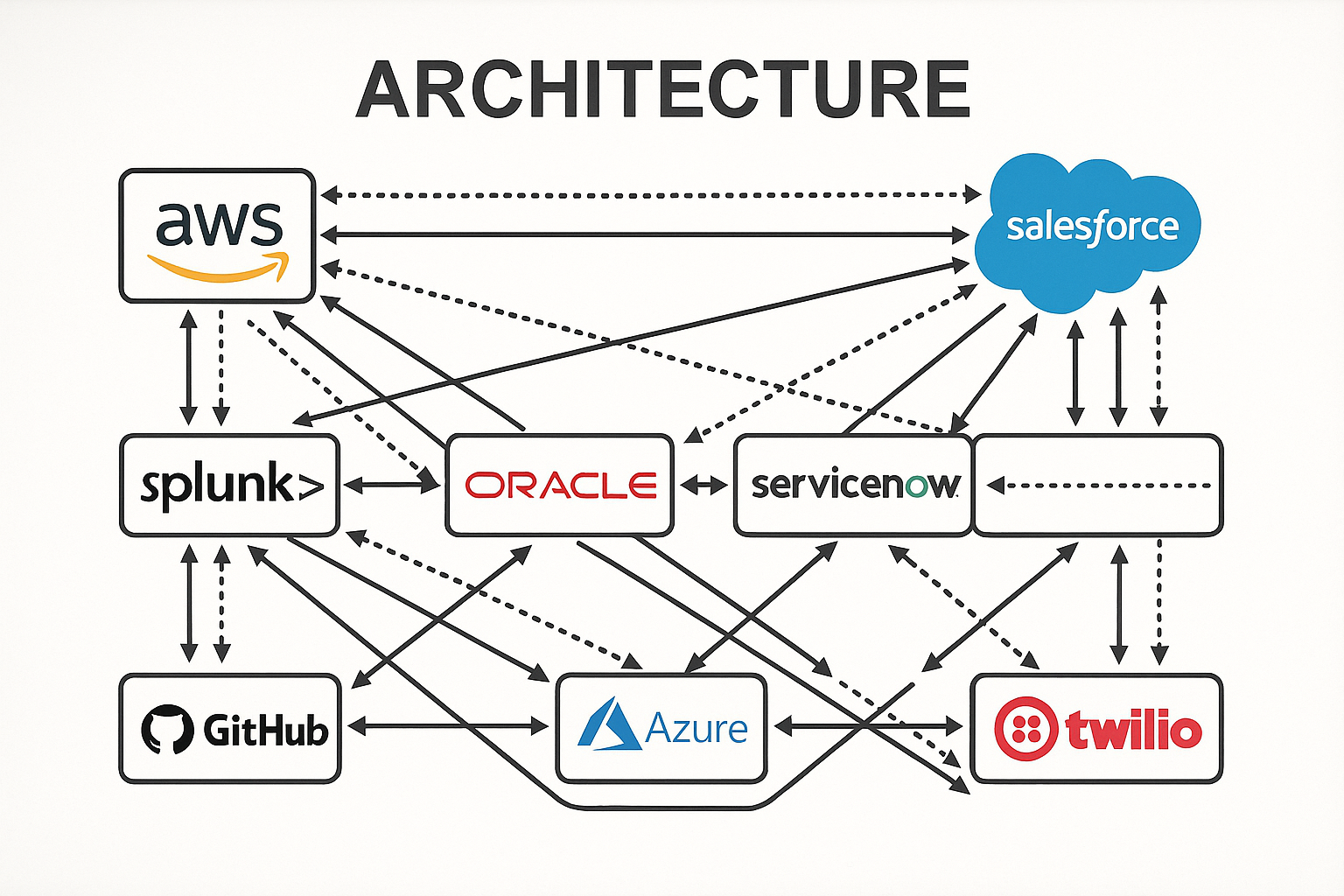

Slide 1: The architecture diagram.

The presenter is excited about the integrations. The audience is lost.

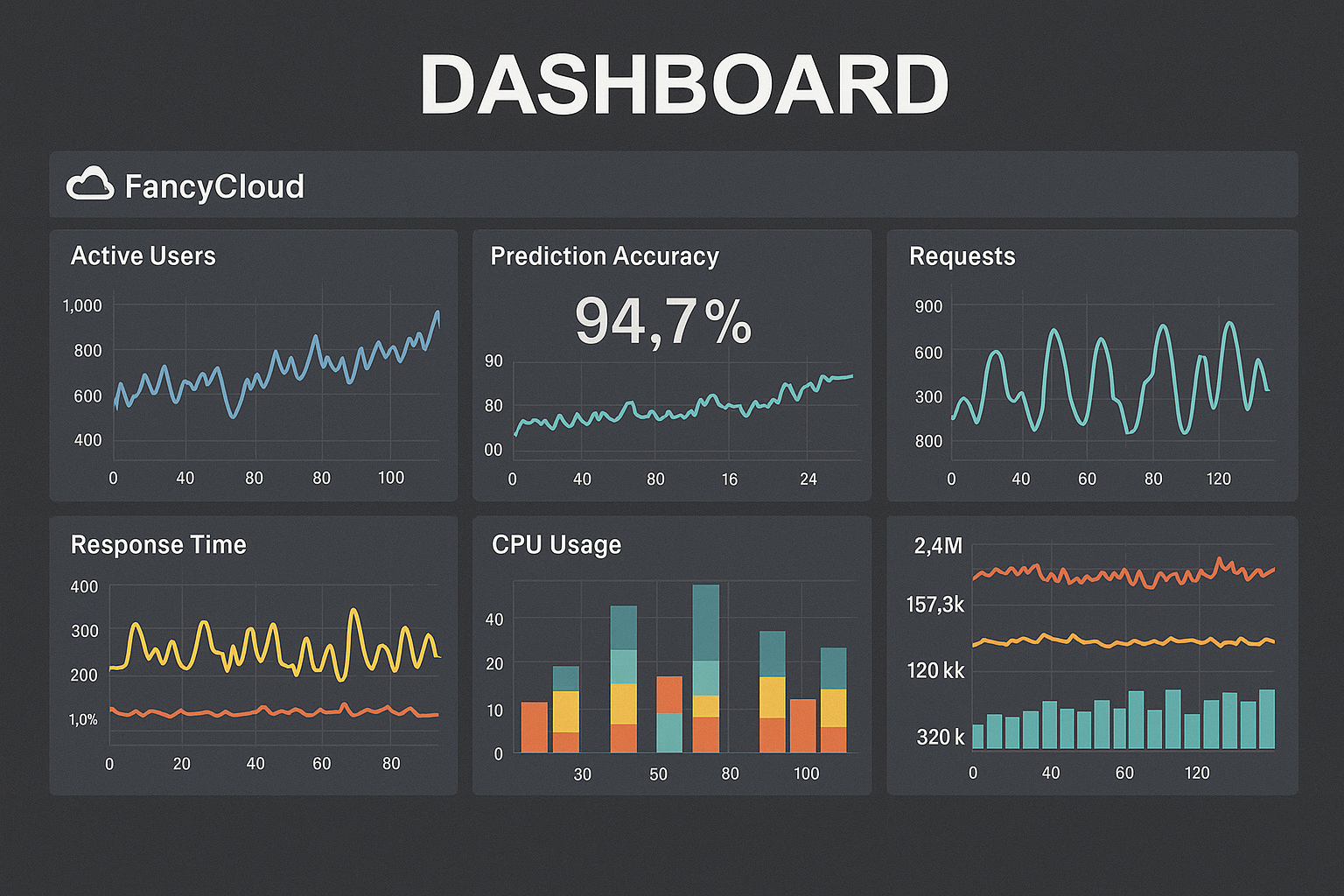

Slide 2: The dashboard.

As you can see here, the prediction accuracy is 94.7%…

Nobody can see. Nobody knows what that means.

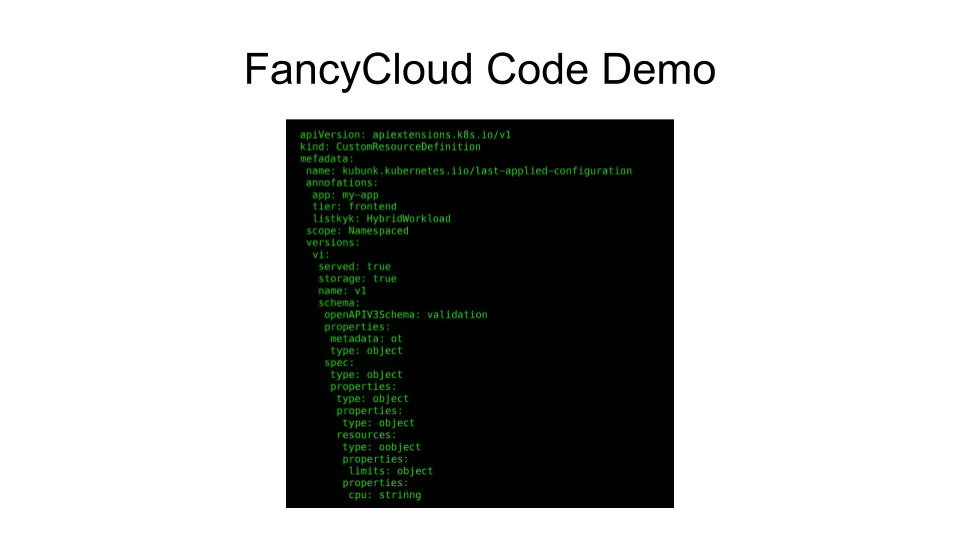

Slide 3: The code demo.

This Custom Resource Definition enables the hybrid workload orchestration…

Half the room doesn’t know what a CRD is. The other half is checking their phones.

Text scrolls. Slides are packed with information nobody can read. People check their raffle tickets, thinking about the Dreamcast they might win for their kid. They’re neither reading nor listening. They’re just waiting for this to be over.

Then someone raises their hand: ‘But what does this actually DO?’

What I just told you is the beginning of a fantastic story. Or rather, it’s a story that is mired in jargon and while clear enough to understand, it does a rather shitty job of piquing the interest of a passerby. It’s the kind of story you tell in the intro of a whitepaper, and nobody reads whitepapers for fun.

If you’ve given a demo like this, you’re in good company. I have too. We’ve all been handed (or rewritten) slide decks, told to ‘show the product,’ and done our best. The problem isn’t us. It’s that we’re following a playbook that doesn’t work.

We’re fifteen minutes in now, and we have no idea where, how, or why they got lost. The demo is clear, obvious, you spent a whole day making it and rehearsing…

And then it’s time to clap, and the lottery begins. Ninety percent of the crowd were never the intended audience. They won’t remember this tomorrow.

That’s how a lot of tech demos begin. The well-meaning presenter will start by spilling out exactly what the product does, WHICH IS OK, but then often goes head down into a tech demo that could put Ben Stein to sleep.

This is the demo gap: the distance between what your solution does and what people understand it does.

Good technology. Bad story. And it kills more good products than bad engineering ever will.

Look, there’s a time for the technical deep-dive. If you’re on a call with engineers who WANT to see the ConfigMaps and CRDs, by all means, nerd out. That’s the right audience.

But at a conference? Most of your audience doesn’t want a technical deep-dive. They want to know if this solves their problem. You owe people more than a lecture. If you’re not converting leads, at least give them a demo worth remembering. Bring a little ZHUSH. Make it good enough that they tell the people who actually need to hear about this to check you out. Not because you’re giving away a Dreamcast, but because your demo was actually worth their time.

The engineers who want the deep-dive will find you. They always do. But first, you have to make them care.

A different kind of demo

The framework

So what works instead? There’s a pattern I’ve used when scaffolding demos for partners. I work with storage vendors, database companies, security platforms. The products are different, but the structure that works is always the same:

- Meet the person

- Show the nightmare

- The moment of pain

- The magic

- The measurable result

That’s the structure. Here’s what it looks like in practice.

Let me show you how this works with a demo I built specifically to teach this framework.

CloudCritters

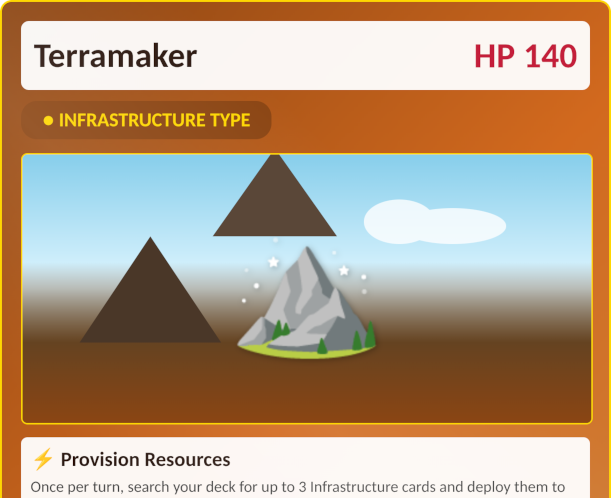

I built a collectible card game called CloudCritters. It’s a fictional trading card game about building cloud infrastructure. You read that correctly. The game has resources to be provisioned, decks to build with infrastructure, storage, network, and chaos events. Each card has abilities, synergies, and weaknesses.

CloudCritters doesn’t exist to sell booster packs. I built it to demonstrate this framework, and it’s open source. Even when the gap is absurdly wide, like cartoon cards translating to fraud detection or security posture analysis… if this works, your demo will work even better.

Meet Riley

Riley just found a deal: 1,000 mixed CloudCritters cards on eBay for $200. No listing, no pictures in the description. She knows that even if it’s mostly commons (the cheapest card classification), she’s not getting fleeced. Good gamble. She clicks “Buy it Now.”

A week later, Riley has a box of cards to evaluate, enumerate, organize, and optimize. I hope this sounds relatable to you in some way.

The nightmare

Riley dumps the cards on her table. She needs to build a tournament-legal deck. That means:

- Identifying which cards she actually has

- Finding cards that synergize (work together)

- Building around an anchor card

- Making sure none are counterfeits (tournament judges will disqualify fakes, and they tank resale value)

She spots Terramaker in the pile. That’s her anchor (could’ve been OpenSlice, BIG-SEGMENT, or any other foundation card, but Terramaker is what she pulled). She knows if she starts there, she’ll have a viable strategy.

But here’s the problem: she can’t evaluate 1,000 cards manually to find the optimal combination. She doesn’t know which cards in this pile synergize with Terramaker. In 2025, she’s not spending hours cross-referencing wikis and tournament data.

The moment

Riley opens DeckBuilder AI. She spreads the cards on her table and takes a photo with her phone (maybe two or three, depending on the pile).

Build me the best tournament deck using Terramaker as the anchor.

The magic

DeckBuilder AI analyzes the image:

- Inventories all 1,000 cards

- Queries an open database of CloudCritters cards to understand how they work

- Identifies synergies: “You have 2x Storagekeeper and 1x Networkweaver. These work with Terramaker”

- Flags counterfeits by comparing against known authentic images

- Builds an optimal 50-card deck

- Warns: “Your deck is vulnerable to Configuration Drifter. You need Version Control cards. You don’t have any. Buy 2x Version Control to shore up this weakness.”

Thirty seconds later, Riley has:

- A tournament-legal deck

- A shopping list for the 3 cards she needs to buy

- Confidence that her expensive cards are authentic

The tech

This uses computer vision, semantic search, and constraint-based optimization. The system identifies cards via object detection and OCR, queries a vector database for card relationships and tournament data, then generates an optimal deck configuration given Riley’s constraints (her collection, tournament rules, the meta).

The enterprise translation

Security vendor: A network security platform needs to recommend optimal firewall configurations. Given an organization’s existing infrastructure (Riley’s card collection), compliance requirements (tournament rules), and threat intelligence (the meta), the system generates a configuration that maximizes protection while minimizing false positives. Same constraint-based optimization. Different domain.

Storage vendor: A storage platform optimizes data placement across hybrid cloud infrastructure. Given available storage tiers (Riley’s cards), access patterns (synergies), and cost constraints (budget for singles), it generates a tiering strategy that maximizes performance while minimizing cost. Same optimization. Different domain.

Your product isn’t a card game

This demo is built around a card game some of you consider silly. That’s fine. Your technology stack is different. It’s in an entirely different domain. That’s the point.

If cartoon cards about infrastructure can demonstrate semantic search and constraint-based optimization, your grounded demo will work even better. The technology is identical. The story just changed.

Choose your own MacGuffin

Reality is, you’re not going to use cartoon cards to demonstrate your product. CloudCritters is deliberately outrageous. It exists to prove the framework works even at the extremes.

Your MacGuffin can be realistic. Introduce Terry, the data analyst. Lupo with an escalation at 3 AM. Apoorva the CFO staring at ridiculous metered cloud bills. The point isn’t the name or the game or the role or the props. It’s the human story and the way you describe how your product is the answer to their problem.

Show the code. Demonstrate the architecture. Just sequence it AFTER the story. If you’ve got 40 minutes and you load the powerful human story at the front, you’ve got my attention. I’ll stick around for the live demo. Bonus points if you make me take out my phone and interact with your demo myself. Whatever you do, make it engaging.

If you have less time (a lightning talk, maybe), the deep-dive is a “meet me at the booth” activity or a QR code you share for later.

And sure, we can keep the logos for a backdrop. Everyone loves branding. But we probably don’t need the floating arrow diagrams.

The framework works whether your McGuffin is cartoon cards or a data analyst with a real problem. What matters is the human at the center. And right now, that matters more than ever.

Why this matters now

Reflecting on the last several conferences I’ve attended, most of us are working on AI integrations. The literacy gap is positively massive. Nearly everyone has “played with ChatGPT once” and some of us have “run ML infrastructure,” but the people who live in the space between are varied and unique. You’re talking to vibe coders, people debugging existential crises with ChatGPT at 2 AM, people who have replaced Google searching with Claude or Gemini. You might be talking to me, working on integrations between platforms and partner technologies.

The importance of the demonstration, arguably the importance of any interaction, is connecting with the individual in your audience.

The technical decision happens inside the demo gap. It happens before the formal evaluation. Our customers will tell us later how their problem is unique, how their stack is built, how it scales. They’ll ask for a proof of concept and collaborate with us to determine if our technology interfaces with theirs.

But first, we have to get ahead of how technically impressive our product is and help the decision maker see themselves and their team in our demo.

This isn’t about dumbing down the demo. It’s about sequencing it so the technical sophistication is earned, not assumed.

The practical toolkit

The next time you’re building a demo:

- Find your person. Give them a name. Understand their role. Not the technical decision maker, the end user. What do they say when they’re frustrated?

- Make it concrete. Not “documentation is hard.” Instead: “Doreen spent 20 minutes grepping through PDFs at 2 AM.” We spend so much time thinking about technology. We owe a debt of time to the human interfacing with it.

- Strip the architecture. Save the branding and logos for a few minutes later. Give the human connection time to breathe. Bring in the diagrams AFTER the audience is engaged with your story.

- The 30-second test. Can someone who walked in late still engage with your presentation? If they need context, your framing needs work.

- Build the translation bridge. After I gave you Riley’s story, you bridged her problem space with one of your own invention. That’s the magic of a functional demo. Once they understand the relatable version, the enterprise version should feel obvious.

The story is the work

The conference demo playbook is broken. It presumes technical sophistication, leads with architecture, and loses the room before the value is clear. It suffers from years of endlessly copied slide decks and tiny changes until it’s become an amalgam of artifacts followed by a UI demo and pleading for questions.

What’s happened now, I hope, is that you’ve internalized the framework. You found the friction (Finding Your AI North Star). You solved the problem in a novel way. Now you’re connecting it back to the source of that friction, only now, in story form.

We found the human in Riley. Her nightmare was clear. We demonstrated the transformation from problem space to effective workflow, and the tech stack became obvious without overwhelming the audience. That’s the pattern: find the human, show the nightmare, demonstrate the transformation, make the technical choices obvious in retrospect. Give them something memorable: Riley, CloudCritters, whatever works for your domain.

The technical part is easy. The story is the work.