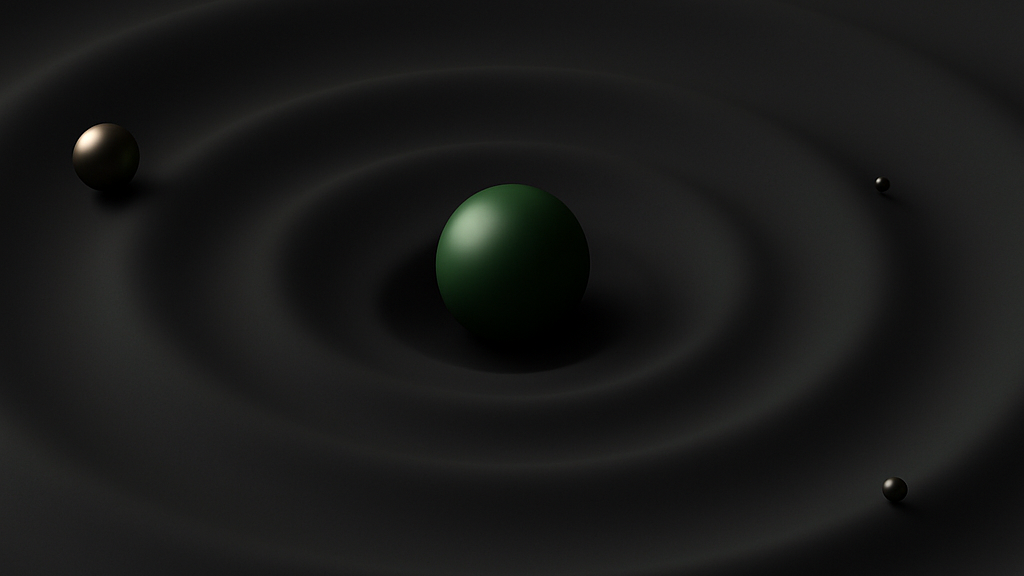

Workplace hierarchies are gravity wells

and they suck more than you think

This is a considerably longer piece than I intended to write. Workplace hierarchies is a complex topic that is impossible to cover well in 1000 words. I encourage you to grab a cup of tea and settle into this one, it will probably resonate with you better that way.

The casual greeting

I had a conversation with two workplace peers, previously unknown to me, during KubeCon North America last week. During that conversation, the natural introductions extended into “so what do you do?” I mentioned my title and briefly described my role, another did the same. Our third friend, deliberately last, mentioned under his breath “VP.”

We’ve all experienced interactions with people at various administrative levels. Maybe you’ve been through enough therapy or personal soul-searching to confidently say you exhibit no difference in mindset or behavior in the company of those significantly senior to you. If none of this sounds familiar, you might be the one changing the air.

Whether you are the VP yourself, the newer employee, or the tenured individual contributor, at one time you’ve been comparing ideas with teammates or with organizationally unrelated peers in different dynamic environments. In our specific case, we were in the middle of sharing observations about trending topics that dominated the conference. The conversation had the easy rhythm of peers who speak the same language. Then the air changed.

When people have no context clues to assume power differentials, discussions can flow naturally and unrestricted. You can speak freely, knowing your place in the perceived hierarchy is safe. As soon as that hierarchy is laid bare, people suddenly protect their reputation and project their value in subtle ways. Contributions they may normally make in safety are withheld in case they might be perceived as weak or ignorant. Others may be gated or conditioned to avoid the appearance of being too bold, if they become articulated at all rather than deferred.

This is what matters for this piece: not the person’s title itself, but what happens in the space between hearing it and pretending it doesn’t matter.

What that moment reveals

Here’s what we tell ourselves: titles are just organizational scaffolding. They denote different responsibilities, not different worth. In functional teams, hierarchy flattens naturally around technical problems because the best idea wins, regardless of who said it.

Here’s what actually happens: participants evaluate the people in the room and assign weight to those people’s contributions or reactions to their own. If they feel shaky or less than confident about their own ideas, they’ll defer or condition them because they privately want the approval of the person or people creating the gravity well. They’ll agree, coolly or emphatically, with ideas they wouldn’t normally care about or in some cases, actively disagree, because the perception of being agreeable to the vision of those with greater influence is safer than developing a reputation as a rabblerouser.

Titles don’t just define, they distort

Every organizational chart creates invisible force fields around certain roles. When a VP enters a working session, people don’t just acknowledge their presence - they recalibrate their participation. They:

- Edit strong technical opinions into suggestions

- Frame disagreements as questions rather than counter-arguments

- Wait to see which direction leadership is leaning before committing to a position

- Mentally calculate whether speaking up is worth the perceived risk

None of this is conscious. Nobody wakes up and decides “today I will defer to hierarchy.” It’s a learned response to organizational power structures that punish dissent - or reward alignment - in ways both subtle and overt.

The marginalization multiplier

If you’re a manager reading this thinking “my team doesn’t do that,” consider who’s most likely to self-censor when hierarchy enters the room:

Women and underrepresented minorities face a tax on advocacy that others don’t pay. A woman who pushes back on a VP’s technical direction risks being labeled “difficult” or “not a team player” - descriptors rarely applied to men exhibiting identical behavior. This example in particular is not limited to the reality of titles, either. I’ve personally observed this, and had people privately appeal to me about it, many times: dominant personalities who mistake volume for expertise, or who subtly bully women and minorities into passive roles.

H-1B visa holders aren’t just risking their job when they disagree with management, they’re risking their ability to remain in the country. The stakes are existentially different. If you as a manager think your visa-holding direct reports are giving you their unfiltered technical opinions, you’re probably being overly generous about your own views on accessibility.

Junior contributors learn quickly that “we value all voices” is rhetoric that doesn’t survive contact with reality. When the senior architect or director speaks first in a design review, the game is already over. Everyone else is just playing probability: what’s the safest way to agree without looking like they’re just agreeing?

This isn’t just uncomfortable. It’s expensive.

The real cost

Tech companies love to talk about flat organizations and open cultures. They put it in recruiting materials. They mention it in all-hands meetings. Then they structure themselves exactly like every other hierarchy and wonder why the best ideas die in Slack channels instead of making it to production.

You’re losing technical leverage

The person closest to the problem usually has the best solution. That’s not inspirational, it’s mechanical. The engineer debugging the authentication flow at 2am has pattern-matched failures you’ll never see in a dashboard. The support engineer who fields the same confused question seventeen times a day knows exactly where your UX is broken.

But when those people calculate that surfacing their insight means contradicting someone three levels above them, they stay quiet. Not because they’re cowards - because they’re rational actors in a system that’s shown them the cost of being right at the wrong time.

One story I heard roughly a year ago involved an individual contributor who observed a recurring problem: customers were abandoning their company’s product for a competitor’s solution to work around a specific workflow issue. Using a direct anecdote would necessarily identify the companies involved, so I apologize for speaking in generalities which I hope will get the point across. This person escalated a viable fix to the product team - one that would have resolved the problem and prevented handing business to a competitor.

The response? Lukewarm. No resources. No follow-up. The idea died in a backlog somewhere.

Over a year later, and after months of water-cooler pressure, a VP presented a very similar solution. It was developed, marketed, and successfully restored confidence in the original product. But only after considerable time, revenue, and reputation had already been lost because of hierarchy pretending to be process.

The problem wasn’t the idea. The problem was who said it first.

DEIA becomes performance art

Diverse teams outperform homogeneous ones when diversity of thought translates to diversity of input. If your org chart reflects commitment to inclusion but your meeting culture ensures only certain voices get heard, you’ve built an expensive monoculture with better optics.

The most insidious version of this: leaders who genuinely believe they’re creating space for all voices while unconsciously applying different standards for whose ideas get taken seriously. For example, you may have contributors on your team who channel a great deal of passion, and rightly so, when they feel a direction has a significant impact on product or operations. One tendency which can be difficult to detect is to dismiss this as an emotional response in order to move on to something else.

Another pattern, almost imperceptible unless you’re calibrated to it: the personal compliment that sidesteps the idea. “You’re so articulate” instead of “that’s a solid proposal.” “I love your energy” instead of engaging with the technical argument. These aren’t compliments, they’re dismissals wearing friendlier clothing.

Your best people leave

High performers leave when they realize the game is rigged, and they rarely tell you why. Exit interviews are theater. Here’s what’s actually happening.

Sometimes your best talent will quit because better ideas lose to worse ones that came from higher up the org chart. Sometimes they leave because they watched a blowhard get promoted over them not because of merit, but because confidence theater looked like leadership to people who couldn’t tell the difference. Sometimes they quit because they’re not getting promoted fast enough and they’ve done the math… at their current company, advancement requires playing politics they refuse to play.

The common thread isn’t “meritocracy failed.” It’s “the culture didn’t match the LinkedIn page.”

When you tell people that ideas matter more than titles, then promote based on volume rather than signal, you’ve taught them that the culture you advertised doesn’t exist. When you say “we value technical excellence” but the person who gets the architect role is the one who talks the loudest in design reviews, you’ve shown them what you actually value.

They leave because “open culture” turned out to mean “open to hearing you, not open to listening to you.” Or because it meant “open to whoever can perform confidence the most convincingly.”

What actually works

If you’re in a leadership or management role, your job isn’t to be the smartest person in the room. Your job is to make the room safe and rewarding enough that the smartest people will speak.

This is also the appropriate time to mention that leadership and management do not strictly refer to title and job function. They also refer to your own role and personal responsibility as a steward of the culture you want to promote among those you influence. All of the following points refer to you, whether you are a people manager or not.

Flatten the room actively

Hierarchy doesn’t disappear just because you say “let’s keep this casual” before a meeting. You have to actively counteract it:

- Speak last, not first. When you open with your opinion, everyone else is now responding to your framing instead of bringing their own. If you must speak early, make it a question: “What are we missing here?” not “Here’s what I think we should do.”

- Interrupt yourself. When you notice the room deferring, call it out: “You don’t need to worry about my approval, Shane. You’ve been quiet and you know this relationship well. What do you think?”

- Defend dissent publicly. When someone challenges your idea, your job is to engage with the challenge substantively, not shut it down. “That’s an interesting point” is not engagement. Instead, try “Walk me through why you think that approach would fail.”

Advocate upward with attribution

When your reports have the right answer, champion it in skip-level meetings and make damn sure everyone knows whose idea it was.

Not: “We’re refactoring the API gateway.”

But: “Jordan identified a bottleneck in our API gateway that’s costing us 200ms per request. They proposed a refactor that should cut that by 80%. Here’s their design doc.”

Your positional authority exists to amplify your team’s authority, not replace it. Use your credibility to make sure your reports’ ideas get the same serious consideration that a VP’s ideas would get automatically.

Better yet, create opportunities for them to present their own work to leadership. Your job isn’t to be the translator. It’s to prepare them not to need one.

Create safety for the people who need it most

For visa holders: Make it explicit that technical disagreement is not only safe but expected. “I need you to tell me when I’m wrong” isn’t enough. You need to demonstrate that disagreeing with you has no professional consequences, which means when someone does disagree, you visibly value it. In front of others. On the record.

For women and underrepresented voices: Notice when you’re applying different standards. When a woman advocates strongly for a technical position, is your internal response “she’s being difficult” or “she’s being thorough”? When a man does the same thing, what label do you apply? When someone is spoken over, do you interrupt and redirect: “Hold on, let Sarah finish her thought”?

For junior contributors: The newest person in the room often has the clearest view of what’s broken precisely because they haven’t been acculturated into accepting your dysfunction as normal. “That’s how we’ve always done it” is not a defense, it’s an admission that you’ve become numb.

Guide without dictating

Constructive feedback is not about asserting your judgment over another. It’s about helping people observe blind spots and sharpen their thinking.

Develop a “traffic circle” approach rather than a “red light” one when working with your cohorts. Instead of suggesting something like “That approach won’t work, here’s what you should do instead,” try “I’ve seen similar approaches fail when X happens. Have you thought about how you’d handle that case?” In this way, you allow reasoning to flow continuously instead of forcing a stop-start cycle.

The goal is to help them arrive at better solutions, not to make them execute yours.

What this looks like in practice

Theory is easy. Implementation is where most of this dies. Here’s what actually flattening hierarchy looks like, and what you ultimately want to see.

“I disagree” becomes a complete sentence

In healthy teams, technical disagreement requires no preamble, no softening, no apology.

Not: “I might be wrong, but have we considered…”

But: “I disagree. Here’s why.”

If people in your org can’t say that to you without adding fifteen words of cushioning, you don’t have a flat culture. You have a hierarchy that’s learned to be polite about itself.

Managers defer to technical experts publicly

When someone on your team knows more than you about a domain, which should be often, say so out loud. In meetings. In Slack. In front of skip-levels.

In my role in front of partner leadership, I’m frequently expected to be a subject matter expert on an impossible range of domains. When I’m out of my depth, which is often, I say so: “I don’t know this area well enough. Let me bring in Charlie who owns this.” That’s not self-deprecation. It’s making it normal to acknowledge expertise independent of title.

The room is structured for inclusion

“Everyone’s voice matters” is hollow if your meeting structure ensures certain voices won’t be heard.

- For larger meetings, always have an agenda or at least a topic overview. Pre-reads give people time to formulate positions instead of reacting in the moment.

- Round-robin discussions where everyone speaks, with a signal to indicate intention. For example, a raised hand, or one hand flat on the table, instead of an “open floor” where extroverts dominate.

- Async decision-making documents where people can contribute without performing in real-time. This allows people with social anxiety to participate without spinning out in front of their peers.

Skip-levels flatten hierarchical information asymmetry

Skip-level meetings exist to create understanding that can’t happen through the management chain alone - and when done right, they actively counteract the distortion that titles create.

If you’re the senior leader: You’re not there to evaluate or assert your position in the hierarchy. You’re there to understand what’s actually happening at the implementation level: the friction, the unclear decisions, the patterns your direct reports might not see or might be filtering because they think you want good news. This is where you demonstrate that hierarchy doesn’t apply. Ask about obstacles and context, not deliverables. “What’s confusing right now?” not “What have you shipped?” When a report surfaces a problem, your job is to remove the barrier or explain why it exists, not to defend the status quo because it came from above.

If you’re the report: This isn’t a job interview or a chance to manage up. It’s an opportunity to give your skip-level the ground-truth perspective they can’t get from dashboards or your manager’s status updates, and to test whether the “flat culture” messaging is real. Surface the things that are working, the things that aren’t, and the questions you have about broader direction that feel too risky to ask in larger forums. Your manager should have prepared you for this and made it clear that candor is expected, not punished. If they haven’t, that’s useful information too.

The goal: These meetings should erode the “they’re too senior to hear this” instinct that hierarchy breeds. Your skip-level should walk away understanding your reality in a way that helps them make better decisions. You should walk away understanding the broader context for why certain priorities exist, and feeling like your perspective mattered regardless of your title. Neither of you should be performing.

The blind spots you can’t see alone

Even with the best intentions, you’re going to miss things…

Meritocracy blindness

If you believe you run a true meritocracy, you’re probably wrong. The Tech Lead who thinks they’re “just another engineer in the discussion” can’t see how their presence changes the room. Everyone else is editing in real-time based on what they think you want to hear.

Ask yourself: when was the last time someone on your team told you that you were wrong about something technical and then had to convince you? If you can’t remember, either you’re never wrong (unlikely) or people have stopped trying.

The ‘we value all input’ lie

Saying “everyone’s voice matters” while letting the VP speak first is performative. People pattern-match to hierarchy. If you want actual flat discussion, the most senior person speaks last, or doesn’t speak at all and just asks questions.

The context trap

“They don’t have enough context” is the most common excuse for dismissing ideas from junior contributors. Sometimes that’s true. More often, it’s a way to avoid engaging with an uncomfortable insight.

This was mentioned before but it’s important enough to bear repeating here: new people see your broken processes clearly because they lack context. They haven’t normalized the dystopia yet.

I’d bet money there’s some trivial annual process in your org involving hard-to-find forms and undocumented approval paths that exists purely as tribal knowledge. Even the people who know how to navigate it curse under their breath every time they encounter it. When the new hire points this out, and especially if they propose a fix, that’s not naivety. That’s someone who hasn’t yet learned to accept the broken normal. Embrace it. Fix the process. Give them credit for it.

Why this matters beyond your org

Earlier this year, I attended a tech conference in London where several talks focused on biased training data in AI models - how those biases led to massive disparities in outcomes for underrepresented people. I’ve spent many evenings since then thinking about how bias compounds across systems, and how the same dynamics play out in our workplaces.

The pattern is familiar: loud, confident voices - disproportionately older white men in tech - dominate the conversation. Everyone else learns to navigate around them or gets sidelined. There are exceptions, but when you compare minority representation against the general population, then narrow it to technology professions, then narrow it further to recognized leadership, the disparity is glaring.

This piece isn’t primarily about DEIA, even though DEIA is inseparable from the problem. This is about power dynamics and what they cost us. When hierarchy determines whose ideas get heard, you’re not building the best product. You’re building the product that survived the internal politics.

Technology doesn’t advance because executives have good ideas in strategy meetings. It advances because the people closest to the problems had the safety and support to solve them. Some companies have figured out how to flatten hierarchy without flattening accountability - where “I disagree” doesn’t require fifteen words of cushioning, where managers advocate for their reports’ ideas with conviction, where the newest person can point out problems without calculating career risk first.

This isn’t utopian. It’s mechanical. When you remove barriers to good ideas surfacing, better ideas surface.

Back at KubeCon, after the air changed, I didn’t stop talking because the conversation died. I stopped talking because I suddenly became aware of my own calculus: Is what I’m about to say impressive enough? Has he already heard this from someone more senior?

I’d been holding my own just fine. Then the VP reveal happened and I started editing in real-time. I trailed off. Found a polite exit. Moved on to safer ground.

The conversation didn’t fail because hierarchy killed it. It failed because I let it.

And I’m a middle-aged, cis-het white guy, with senior+ bona fides. All the privilege in western society. If I’m self-censoring based on professional hierarchy, imagine: what it’s like for people who have actual reasons to worry about the cost of speaking up?

You don’t need overt power plays for hierarchy to do its work. You just need people who’ve learned to calculate risk before they speak.

An impressive title will change the air in the room. That’s mechanical, not fixable. What you can fix is what happens next: whether that change creates deference, or whether it creates space for honest technical discourse that actually moves things forward.

You can’t eliminate power dynamics. But you can decide whether they define your culture. The difference is whether you’re willing to do the uncomfortable work of flattening the room - even when you’re the one with the title that changes the air.